Written by NDA senior tutor, Vicky McClymont

As a design school, we at the NDA are all too aware of the impact and legacy we can impart on our students and on the next generation of designers. However, there is no design school that has had such a great impact and left its mark more so than the world-famous Bauhaus. Here in this blog, we discuss the legacy of the Bauhaus and celebrate, in 2019, the centenary of this prestigious design school.

The Bauhaus building, Dessau – 1925/6, designed by Walter Gropius.

The Bauhaus building, Dessau – 1925/6, designed by Walter Gropius.

A brief history of the Bauhaus

Founded in Weimar, Germany, by Prussian architect Walter Gropius (1883-1969), the Bauhaus was a dynamic think-tank in which the core objective of the school was to provide a unification of art and design; to reimagine the material world to reflect the unity of all the arts (Gropius, 1919).

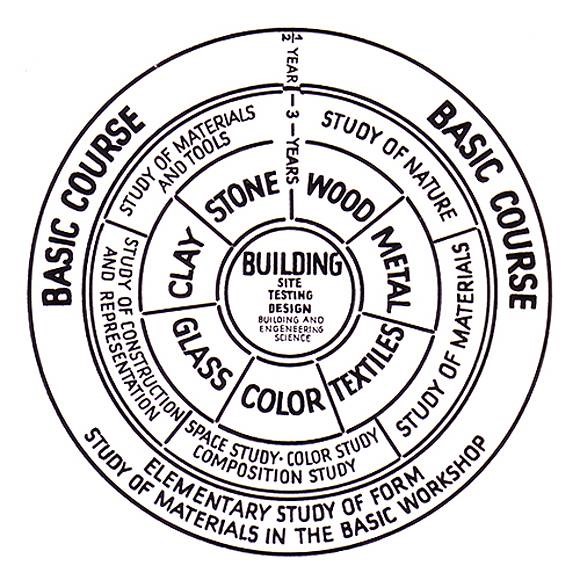

The development of a craft-based curriculum was key to the Bauhaus’ success. Gropius devised a structure of teaching whereby all students would undertake basic training in the likes of colour, shape and materials. From this, students would then undertake practical work in the workshops and accompanying disciplines, eventually focussing on a core subject area. Educational courses with this type of structure were unprecedented at the time, and it is key to note in this structure, that the ‘building’, or ‘Bau’, was at the centre of all activities. The curriculum would aim to produce artisans and designers capable of combining architecture, sculpture and painting into one creative expression, all with the building at the heart of the design process.

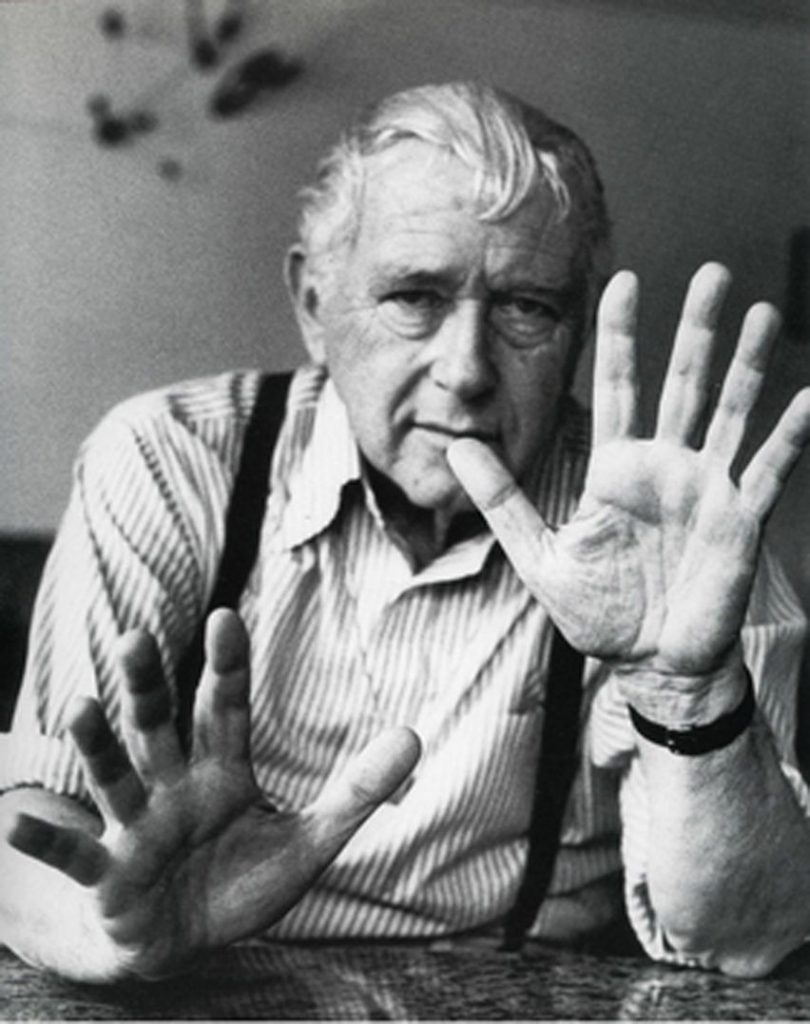

Bauhaus alumni: Marcel Breuer

Marcel Breuer, student turned Bauhaus Master, is amongst a handful of recognisable names synonymous with Bauhaus exploits and subsequent design influence. He joined the Bauhaus in 1919 as one of the first and youngest students. After initially enrolling to study painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, the lack of a ‘hands-on’ approach and an overwhelming focus on theory, led Breuer to immediately heading to Weimar to enrol at the Bauhaus. Here, Breuer worked alongside the likes of Josef Albers on the preliminary courses, eventually focusing his creative approach in the carpentry workshop. It was at the Bauhaus when Breuer had returned as a Master in 1925, that he designed one of his most celebrated pieces of furniture; the Model B3, otherwise known as the Wassily Chair (named after Bauhaus Master Wassily Kandinsky, who upon taking an initial interest in Breuer’s design, was one of the first recipients of a post-prototype model for his office).

Breuer is also widely known for his architectural exploits, but it wasn’t at the Bauhaus where he learnt his craft. Surprisingly, the Bauhaus didn’t have an architectural course in the first seven years of its existence, so Breuer headed to Paris upon graduating from the Bauhaus in 1924 in order to further his studies.

Impressed by Breuer’s innovation and design aesthetic, Walter Gropius succeeded in bringing Breuer back to the Bauhaus in 1925 to take up the position of young master in the carpentry workshop. At this time, Breuer’s experiments with tubular steel continued until he departed the Bauhaus three years later in order to establish his own architectural office in Berlin.

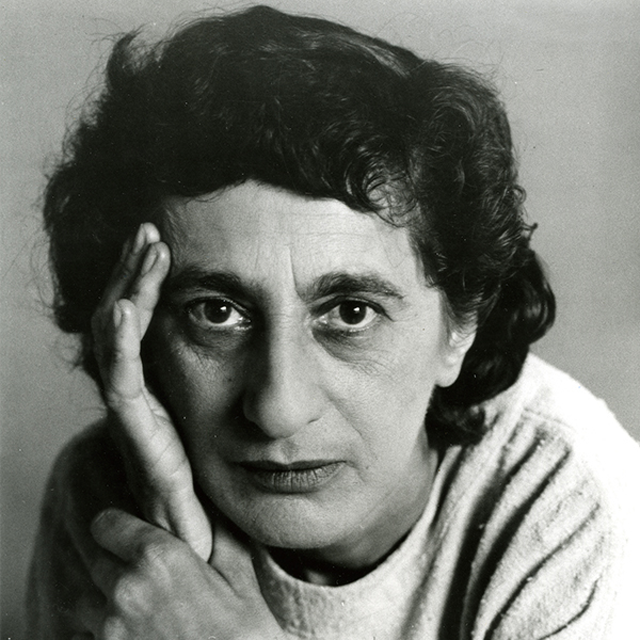

Bauhaus alumni: Anni Albers

The attitude of the Bauhaus towards its female students, when we look from a contemporary viewpoint, could seem surprising. However, at the time, the accessibility of education and certain forms of this were vast in comparison between the sexes. Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius did his utmost to steer female Bauhaus students away from what he called “heavy crafts” (such as carpentry, metalwork, painting and Anni’s preferred subject, glass) to the more “suited” crafts of bookbinding and weaving. Anni selected to develop her studies within the textiles workshop and whilst initially frustrated with this craft, she set about experimenting, turning this traditional medium into “shockingly modern works” (Dezeen, 2018).

Eventually embracing her craft, Anni was soon commissioned to design wall-hangings for Gropius’ new Bauhaus building when the school moved to Dessau and in 1931, was appointed the head of the weaving workshop. By the time the school closed in 1933, Albers, the then-director of the weaving workshop, had utterly transformed the course from romantic-handicraft to students producing pioneering and commercially successful works. Upon the closure of the school, Albers fled Nazism and moved to America, and it was here where a long-lasting collaboration with Florence Knoll was established, with the pair working in association for little over three decades.

The work of Anni Albers has featured in numerous exhibitions over the years, most notably at MoMA with her own showcase in 1949 and more recently, the first major exhibition of her work in the UK, held at Tate Modern (closed 2019).

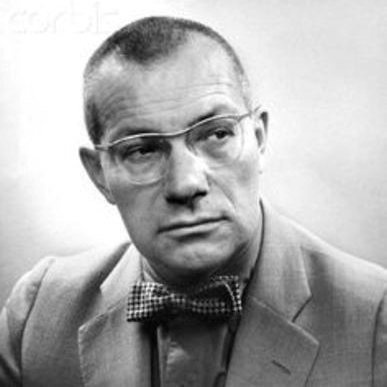

Bauhaus alumni: Max Bill

Architect, artist, painter, typeface, industrial and graphic designer, Max Bill became one of the most versatile designers who emerged from the Bauhaus. Originally undertaking an apprenticeship in silversmithing at the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts, Bill enrolled at the Bauhaus in 1927 in order to study Architecture. It was here, against his protestations, that Bill developed his skill in painting under the tutelage of such distinguished artists as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Laszlo Maholy-Nagy, with the latter stimulating Bills’ interest in industrial design through the introduction of the painting of the De Stijl group and with particular reference to Mondrian.

Bill developed his painting style with great precision; his construction of geometric forms and meticulously planned compositions were all based upon complex mathematical systems. The precision in his work and seemingly straightforward approach to painting became symbolic of his quintessentially Swiss approach to the arts.

Amongst his highly-structured paintings, Bill has become synonymous with his relationship with German watch and clock manufacturer, Junghans. Designing both products and custom typefaces, the first collaboration, Exacta, was released in 1957 with the typeface, numbers and logo all being designed by Bill. This collaboration developed, when in 1961, Bill and Junghans released a series of mechanical wristwatches, which today are still produced and largely unchanged from the original design. The simplicity and purist aesthetic of these watches is a true reflection of Bill’s design ethos.

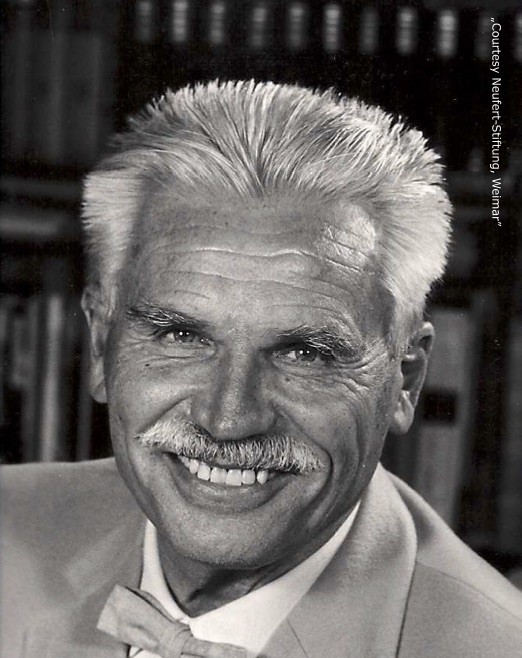

Bauhaus alumni: Ernst Neufert

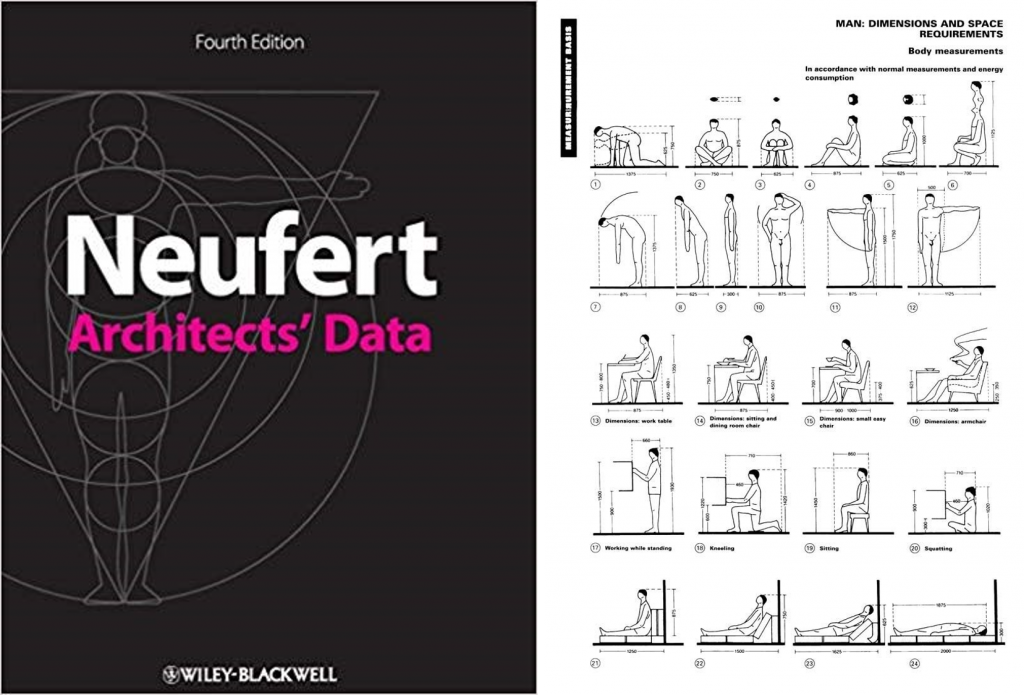

Perhaps one of the most intriguing pieces of research whilst developing this blog, came with the discovery that Ernst Neufert, author of renowned architectural standards book, Architect’s Data, was a student of the Bauhaus.

Originally undertaking an apprenticeship as a mason in 1914, Neufert enrolled as one of the Bauhaus’ first students in 1919. At this time, Neufert was also an employee at the private architectural office of Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer. Neufert’s professional relationship with Gropius continued after the completion of his Bauhaus studies, when in 1921, he returned to the Bauhaus and was employed as a construction site manager, with Neufert overseeing such building projects as the renovation of the Jena Stadttheater, the construction of the new Dessau Bauhaus building and Masters’ Houses.

Early in his studies and eventual career, Neufert recognised the possibilities for rationalisation of building process, but also the need for normative rules. With this, he began developing perhaps his most influential body of work; Architects’ Data. First published in 1936, Architects’ Data is a key reference book for spatial requirements in building design and site planning and today is still used by students and professionals alike in the architectural and interiors industries (including NDA students). Thirty-nine German editions, translated into seventeen different languages, and selling well in excess of half a million copies, the popularity of Neufert’s book is clear to see.

Whilst some have criticised the use of Neufert’s Architects’ Data as a way of standardising furniture to the detriment of those with a shorter or taller than average height, and a way of cutting costs to cater for the majority with little adaptability, there is no doubt of the importance, influence and popularity of Architects’ Data as a way to deliver common benchmarks for ergonomics and functional building layouts.

One hundred years after the opening of the Bauhaus, it is clear to see, still to this day, the influence of the teaching practices, course structure and alumni of the design school upon our current design thinking and output. Throughout 2019, the Bauhaus and its legacy are being celebrated with numerous exhibitions throughout the world, with Berlin hosting a showcase of exhibitions developed in conjunction with The Bauhaus Association.

Follow this link to view a roundup, curated by Dezeen, of sixteen events celebrating one hundred years of the Bauhaus: https://www.dezeen.com/2018/11/26/bauhaus-events-guide-centenary-2019/.

And finally, a short animation entitled ‘Bauhaus: A Visual History’, created by Pam Menegakis, highlighting the key principles and designs of the Bauhaus Movement is well worth a watch!